Month: January 2014

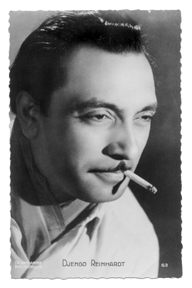

Happy Birthday, Django Reinhardt!

Today marks the 104th anniversary of the birth of the great jazz guitarist Django Reinhardt. He was born in Belgium and lived in Romani (gypsy) encampments near Paris after the age of eight. As a child, he played violin, banjo and guitar, but it was as a guitarist that he made an indelible mark.

Today marks the 104th anniversary of the birth of the great jazz guitarist Django Reinhardt. He was born in Belgium and lived in Romani (gypsy) encampments near Paris after the age of eight. As a child, he played violin, banjo and guitar, but it was as a guitarist that he made an indelible mark.

His accomplishments may be viewed as all the remarkable given he was burned in a fire at the age of 18, causing the fourth and fifth fingers of his left hand to be paralyzed. Thereafter he had to concoct his own unique fingerings for creating chords on the guitar.

As a young musician, Django came under the influence of Louis Armstrong and other jazz musicians, and his musical path was set. Around this time he met violinist Stephane Grappelli, with whom he would soon form the influential combo, the Quintette du Hot Club de France.

Django toured the US in the autumn of 1946 as a guest soloist with Duke Ellington and His Orchestra, but he soon returned to France as some promised solo gigs on the West Coast failed to pan out.

In 1951, he retired to Samois-sur-Seine, near Fontainebleau, though he continued to play gigs in Paris. He was intrigued by bebop and began to incorporate its vocabulary into his playing.

He died of a brain hemorrhage walking home from the Avon train station following a Saturday night gig. He was just 43.

Here’s an all-too-brief clip of Django performing his two-fingered, five-stringed magic:

365 Nights in Hollywood: Subtle Suicide Stuff

SUBTLE SUICIDE STUFF

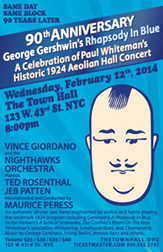

A Gershwin Debut, Revisited

Did you ever wish you could be there for the first performance of an iconic work—say, the debut of George Gershwin‘s “Rhapsody in Blue” as performed by Paul Whiteman‘s orchestra on February 12, 1924, at NYC’s Aeolian Hall on West 43rd Street?

Did you ever wish you could be there for the first performance of an iconic work—say, the debut of George Gershwin‘s “Rhapsody in Blue” as performed by Paul Whiteman‘s orchestra on February 12, 1924, at NYC’s Aeolian Hall on West 43rd Street?

Well, we don’t have a time machine to lend you, but here’s the next best thing. Vince Giordano and the Nighthawks, masters of the sounds of the 1920s and ’30s, are recreating that historic concert in collaboration with conductor Maurice Peress and pianists Ted Rosenthal and Jeb Patten.

Town Hall, which sits on that selfsame block of 43rd Street, is hosting this historic event on February 12th—ninety years to the night after the original concert.

It’s hard to imagine an event that might be considered more of a “don’t-miss.” Get your tickets now!