Did we ever tell you about our family’s minor but memorable role in the legend of the Mother Road, Route 66? No?

Some years ago, our father told us that, in 1933 or so, his parents operated a combination gas station, cafe and motor court right on Route 66 in the western section of Oklahoma City (our hometown, don’t you know). Our recollection is that he said it was west of Portland, not far from where the 66 Bowl bowling alley was for so long (the preceding details are included for those who are familiar with OKC).

Route 66 holds a place of honor in the states through which it passes; it certainly does in Oklahoma. And we count ourselves as Mother Road aficionados; we even drove the entire length of Route 66 in the summer of ’92. So we were very excited to learn that our family had played even a small role in the history of that fabled highway.

And we were even more delighted when Dad filled in some details. His father (our grandfather) was always looking for a leg up, a new scheme to make it big, and that’s why, when he moved his family moved from a farm outside Wayne, Oklahoma, to OKC, they ended up owning (or renting, we’re not sure which) the motor court.

But the story got juicier: Dad told me that not only did the cafe serve beer (we’re pretty sure this all took place during Prohibition, but Oklahoma was a dry state even after repeal), but the rooms were available for shorter stays of, say, an hour or two in length. And yes, that means just what you think it means.

|

|

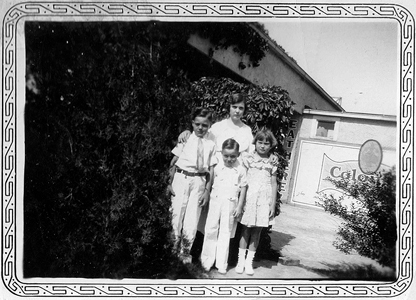

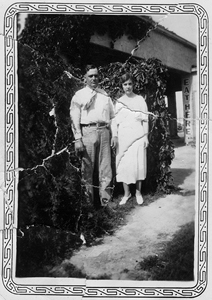

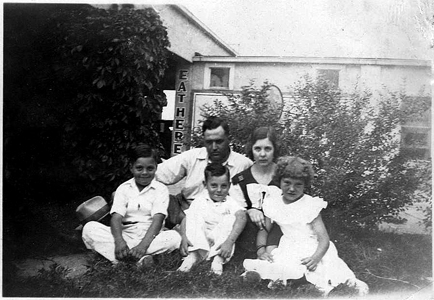

We could not imagine our devout, church-going, teetotaling Grandmother putting up with such nonsense (you can see Grandmother in the photos accompanying these posts—does she look as though she’d be comfortable operating such an establishment?). Dad acknowledged that his mom was none too happy about the family’s new enterprise, but Grandpa was not a man easily denied. It is interesting to note, however, that our grandparents only operated that gas station/cafe/motor court for a year or so, so while Grandpa may have won the battle, it seems that it was Grandmother who won the war.

Spring forward 77 years: Our mom was a go-getter. She got stuff done. But one task she never accomplished was sorting through what she insisted were boxes and boxes of family photographs. When she passed 2010, we finally gained access to those boxes (we never even knew where they were) and we spent hours going through them. While our siblings were more interested in the photos from our own lives, the color shots from the 1960s and ’70s, we were fascinated, it will not surprise long-time readers of this site to learn, by those taken during the first half of the 20th century. We always want to know what we missed! So we were tossing aside all the color shots and going right for the black-and-whites (we’ve shared any number of those with you right here on this website over the years).

And were we thrilled when we came across these photos of Dad’s family posing for snapshots outside that roadside establishment on Route 66! We do wish someone had stepped across the road and taken a shot of the entire layout, but beggars can’t be choosers. We’re very happy to have this photographic evidence of our family’s contribution to Mother Road lore and legend.

|

|