In this chapter from his 1932 book, Times Square Tintypes, Broadway columnist Sidney Skolsky profiles theatrical producer Arthur Hopkins.

SH—SH—SH!!

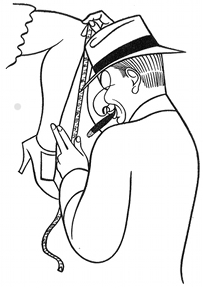

ARTHUR HOPKINS. The sphinx of the show business.

Was born October 4, 1878. His father was a doctor. He has seven brothers. All, with the exception of one, are professional men. The one, William Rowland Hopkins, is at present City Manager of Cleveland. This corresponds to the title of Mayor here.

Is a conservative dresser. Generally wears a derby or gray felt hat. He always wear a bow tie.

He was the first director in America to permit an actor to talk with his back to the audience.

Was once a reporter. Is noted for invading the Polish district of Cleveland and capturing the only photograph of Czolgosz, the assassinator of President McKinley. Every newspaper used this photograph, giving due credit.

He is the author of the book, How’s Your Second Act?

Loves to play golf. Two of his best friends are Sam H. Harris and Arthur Hammerstein. They are known as “the Three Golfing H’s.”

His office is a cubicle room in the Plymouth Theatre. He sits in his chair there, saddle fashion. His desk is piled high with manuscripts. Occasionally he gets reading jags and does nothing for days but read plays.

He is stubborn.

When he first started producing his efforts were rapped by the critics. He said: “I will be producing plays when all those boys are gone and forgotten.” The critics of that day were DeFoe, Reamer, Dale, Davies and Wolf. They are all gone. Years later the same Mr. Hopkins wrote: “I want no praise for bad work. If they find me careless or gross, cheap or vulgar, my head is on the block for them.”

His middle name is Melancthon.

Whenever he discovers what he thinks is an “author” he goes nuts.

Lives in Great Neck. Among his prize possessions there are a baby grand piano, a victrola, his wife—Eva McDonald—and a handsome mahogany poker outfit.

He bought On Trial by giving Elmer Rice a $50 advance. Then produced the play under the Cohan and Harris banner by giving them a fifty percent interest in the play. During one of the rehearsals he thought of the revolving stage. This made it possible to do the now famous flashback in twenty-six seconds.

Gets a big kick out of doing things people don’t expect him to do.

Is more agreeable when he has a flop than when he has a hit.

He never wears jewelry.

When rehearsing a play the stage curtain is always down. He sits in a chair or stands in the wings, smoking. Sometimes it is days before he says a word. For at least seven days the cast merely sit and read their parts. When he thinks that they understand the play thoroughly, he allows them to act. He never tells an actor what to do, but what not to do.

He tells the truth or nothing at all.

Is the only producer who quotes himself in advertisements.

When he produced What Price Glory he thought real soldiers could play soldiers better than actors. Every soldier in that play, with the exception of the principals, had done service abroad.

His great passion is discovering new talent.

Has the ability actually to forget things he doesn’t wish to remember.

He writes most of the statements that are issued by the Producing Managers Association.

On the opening night of a play he does one of two things. He either sits in the light gallery, which hangs over the first balcony, and watches the play and the audience or sits backstage, near the stage door, with his back to the players, listening to the lines and the applause.

His favorite haunt is the Lotus Club.

Once one of his brothers visited him at the office. It is said that both sat there for half an hour before either greeted the other.

He keeps a cow on his estate at Great Neck because he insists on fresh milk every morning.

He knows more than he will talk about. Therefore, is given credit for knowing much more than he says.

The rest is silence.