Here are 10 things you should know about Bebe Daniels, born 123 years ago today. Before she left Hollywood in the mid-’30s, she had appeared in over 270 films, more than 210 of them in the silent era.

Tag: BBC

10 Things You Should Know About Roger Livesey

Here are 10 things you should know about Roger Livesey, born 116 years ago today. His was a prolific career on stage, in movies and on television. He also has one wacky family tree.

The British Bands That Mattered

There are many familiar names among the artists we feature on Cladrite Radio—everyone from Glenn Miller and Louis Armstrong to Billie Holiday, Paul Whiteman, and Nat “King” Cole.

But our greatest pleasure is giving exposure to lesser known artists—bands, singers, and instrumentalists with whom only the true buff is familiar.

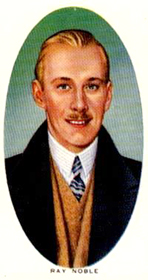

Among those less known here in the United States, except among the cognoscenti, are such British band leaders as Ray Noble, Jack Payne, Henry Hall, and Carroll Gibbons, who was American but gained his fame in England. Each of these artists can be heard here on Cladrite Radio, and those interested in learning more about them now can turn to the BBC’s Radio 2.

|

|

|

|

Air personality Brian Matthew hosts a program called “The Bands The Mattered,” which each week explores the life and career of a pair of orchestra leaders. Payne and Hall were featured in Week 1, but, unfortunately, the BBC only streams each show for a week. But you’ve still got a few days to access the archive of this week’s show, which focuses on Noble and Gibbons.

We only just learned about this program, and we’re not at all happy to have missed the first episode of this season (not to mention all of the episodes of a previous season, too), but we’ll be listening going forward, and we thought you might want to, as well.

Marlowe rides again, via the BBC

We’ve been enjoying “Classic Chandler,” BBC Radio 4’s series of dramatizations based on Raymond Chandler‘s seven published Philip Marlowe novels and Poodle Springs, the Marlowe novel left unfinished at the time of Chandler’s death that was completed decades later by Robert B. Parker, author of the popular series of Spenser detective novels.

We’ll admit that we’re not terribly sold on Toby Stephens‘ Marlowe,. He sounds a bit … insubstantial, to be honest, and his accent is all over the map (view the video below and see if you don’t agree). But that’s a relatively niggling point. The fact that Chander’s unparalleled work is being introduced to a new generation overrides any such objections we might be inclined to raise. Plus, it’s a kick to listen to the kind of radio dramas that once played such an important role in American popular culture but are now so rarely produced (we can’t help but wonder why the radio drama has continued to thrive in the UK and yet is all but extinct on this side of the pond).

We’ll admit that we’re not terribly sold on Toby Stephens‘ Marlowe,. He sounds a bit … insubstantial, to be honest, and his accent is all over the map (view the video below and see if you don’t agree). But that’s a relatively niggling point. The fact that Chander’s unparalleled work is being introduced to a new generation overrides any such objections we might be inclined to raise. Plus, it’s a kick to listen to the kind of radio dramas that once played such an important role in American popular culture but are now so rarely produced (we can’t help but wonder why the radio drama has continued to thrive in the UK and yet is all but extinct on this side of the pond).

The four novels that have already aired are available for listening, free of charge, at the Radio 4 web site, but we wouldn’t recommend putting off giving them a listen. Word is, the links to those free streams will soon come down. (If the links are already gone by the time you read this, the programs are available on CD at Amazon UK.)

The other four novels will air, as we understand it, in the fall.

Speaking of which, that’s one other complaint we have: Why not air the eight novels in the order they were published? Instead, Radio has so far aired, in order, The Big Sleep (the fist Marlowe novel), The Lady in the Lake (the fourth), Farewell, My Lovely (the second), and Playback (the seventh and final novel published during Chandler’s lifetime). It seems an odd choice to air these dramatizations out of order in this way. Playback, adapted from an unproduced Chandler screenplay, is considered by most observers the great writer’s weakest effort—he wasn’t at all well when he wrote it—so saving it and Poodle Springs for last certainly seems the better way to have gone.

But we’re pleased enough to see this series being presented, and we encourage the entire Cladrite community to pop over and give it a listen.

A bird's eye view of 1919

We’re not war historians, by any measure. You won’t catch us watching Nazi documentaries on A&E, and we generally can’t tell one general from another, whether he be Allied or Axis. And the only war history we’ve ever been inclined to read is the work of the late, great Ernie Pyle, who wrote not on the macro level, but the micro, relating the experiences of the common soldier while eschewing more sweeping accounts of battles and campaigns.

We’re not war historians, by any measure. You won’t catch us watching Nazi documentaries on A&E, and we generally can’t tell one general from another, whether he be Allied or Axis. And the only war history we’ve ever been inclined to read is the work of the late, great Ernie Pyle, who wrote not on the macro level, but the micro, relating the experiences of the common soldier while eschewing more sweeping accounts of battles and campaigns.

And if possible, we know even less about World War I than WWII. It’s just long enough ago as to seem out of reach. We don’t really know what caused it and what the end result of it was, other than a simple accounting of the winners and losers. (Hey, we’re not proud of our ignorance here; we’re just being up front about it.)

World War I was fought in such an unusual fashion—all those trenches!—that we too often can’t get our heads around what exactly the participants experienced in fighting it.

This is due in part to the fact that we grew up with World War II movies on the tube constantly. We didn’t watch them terribly frequently, but they were ubiquitous and one couldn’t avoid them entirely. Not so with pictures that depicted the first World War, though we’ve since watched many movies about that War to End All Wars, as our cinematic interest has expanded to include the 1920s and ’30s, when they were made by the dozens.

But perhaps the most moving World War I-related footage we’ve seen dates from the summer of 1919. It was shot by an amateur and on location, not at a studio, using a camera attached to a airplane flying over battle sites along the Western Front and capturing the still-all-too-apparent devastation from above. This footage, shot by a French pilot named (and we’re only guessing at the spelling here) Jacques Tralee de Priveaux, was only recently discovered in a vault in Paris and was included in a recent BBC documentary The First World War from Above. The pilot—we’ll call him Jacques, since we know how to spell that—later joined the French Resistance and was killed during World War II. His daughter, an infant when he died, had only seen photos of her father until she was shown this footage.

Trust us, you’ll be moved by what you see in this clip—by the lingering pain of war that Jacques captured from above nearly 90 years ago, and by his daughter’s emotional first glimpse of her father in his vital and vibrant prime.