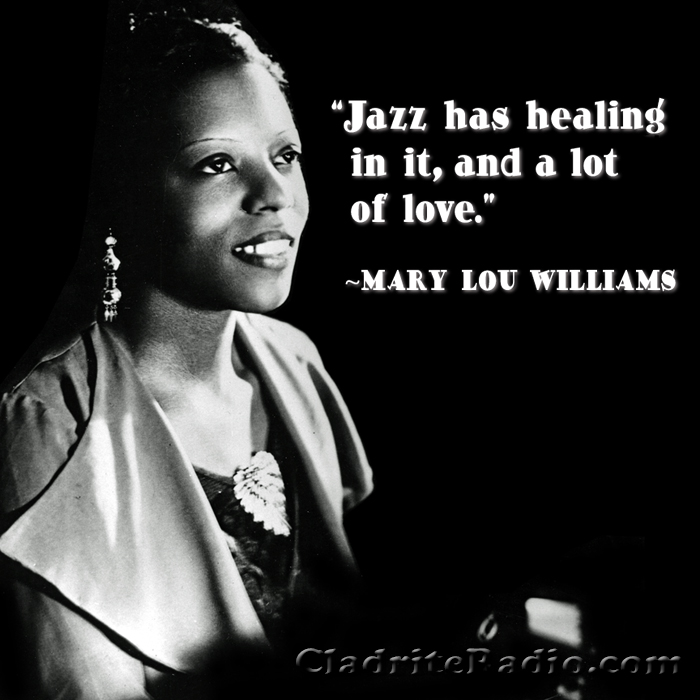

On Cladrite Radio, we proudly feature the marvelous talents of many great African-American artists, performers whose musical gifts have brightened our days, lightened our loads and touched our hearts for decades. It’s painful to think that these giants experienced bigotry, racism and in some cases even physical violence during their lives, and it’s heartbreaking to be reminded that our country’s racist heritage is not yet a thing of the past, that in too many dark corners, it still festers and that precious lives continue to be lost to this hatred.

We want our African-American friends, listeners and followers—and all of our listeners and followers who stand for justice and equality in the US and around the world—to know that we love them, we respect them and we want what they want: a just society that values Black lives every bit as much as all other lives.

In celebration of the great Black artists who have so enriched our lives and in honor of—and solidarity with—those African Americans, past and present, whose lives have been impacted (and too often, ended prematurely) by bigotry and racist hatred, we are, beginning at midnight ET tonight (Friday, June 5), devoting 48 hours solely to music created by Black bandleaders, musicians and singers. We hope you’ll tune in throughout the weekend. #BLM