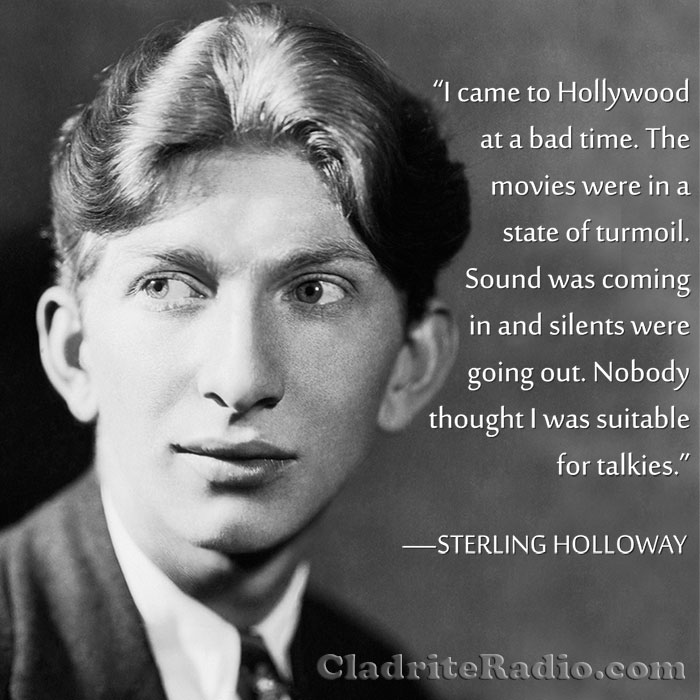

Here are 10 things you should know about Sterling Holloway, born 119 years ago. His shaggy-dog appearance and unique voice made him very much in demand as a character actor.

Tag: Garrick Gaieties

Happy 112th Birthday, Sterling Holloway!

Character actor Sterling Holloway was born 112 years ago today in Cedartown, Georgia. Here are 10 SH Did-You-Knows:

- Holloway was the first of two sons born to grocer (and Cedartown mayor for one year when Sterling Jr. was seven years old) Sterling P. Holloway, Sr. and his wife, Rebecca.

- Holloway graduated from Georgia Military Academy in 1920 and though only 15, he immediately left the South for New York City to attend the American Academy of Dramatic Arts (Spencer Tracy was a classmate and friend).

- In his late teens, Holloway joined a touring company of The Shepherd of the Hills, performing in a series of one-nighters out west. Afterwards, he returned to NYC, where he performed small roles in Theatre Guild productions. He also was cast in the Rodgers and Hart review The Garrick Gaieties, in which he introduced the popular standard Manhattan.

- In 1926, Holloway moved to Hollywood to pursue a career in pictures, and he would go on to appear in 100 of them. His bushy red hair and prominent features made him a natural for comedies, and he got his start in silent pictures, appearing in three shorts and one feature (Casey at the Bat [1927]).

- In 1932, after four years without a film role (a director had reportedly told him he was “too repulsive” for silent pictures), Holloway began to work in talkies, where his high-pitched, chalky voice served him well, and he kept very busy indeed. From 1932-35, he averaged 10 pictures (some of them short subjects) a year.

- Over the course of his 50-year, Holloway appeared in (or did voice work for) more than 100 features and shorts, and made nearly as many television appearances.

- In addition to his picture and television work, Holloway worked frequently on radio, a medium to which his unique and memorable voice was well-suited. Among the shows to which Holloway lent his talents were The Railroad Hour, The United States Steel Hour, Suspense, Lux Radio Theater and Fibber McGee and Molly.

- Holloway was one of the first actors to make the jump to television, appearing in 1949 on the anthology series Your Show Time, which featured half-hour adaptaions of literary short stories from the likes of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Henry James and Robert Louis Stevenson. It was the first American dramatic series to be shot on film and the first series to win an Emmy award.

- Holloway frequently did voice work for animated features, including Dumbo (1941), Bambi (1942), Alice in Wonderland (1951), The Jungle Book (1967), The Aristocats (1970) and perhaps most famously, he provided the voice of Winnie the Pooh in Disney’s popular series of Pooh featurettes.

- College Street, where the Holloway family resided in Cedartown, is now called Sterling Holloway Place and there’s a plaque at the site of his boyhood home.

Happy birthday, Sterling Holloway, wherever you may be!

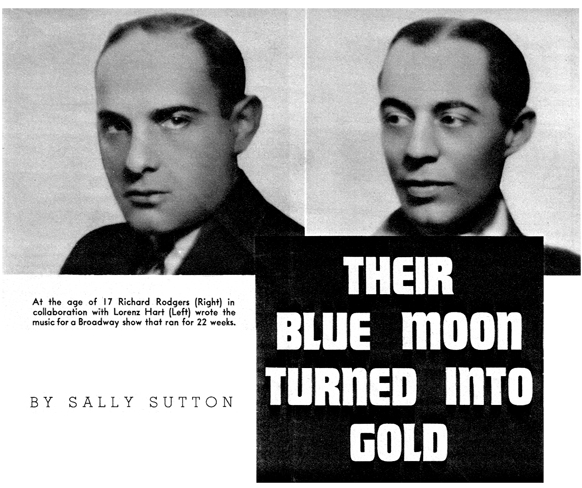

Snapshot in Prose: Rodgers and Hart

This week’s Snapshot in Prose visits a pair of classic composers who need no introduction, Lorenz Hart and Richard Rodgers, when they were at their most successful.

The author of the story speaks to both men, and we learn that they were of very different temperaments, outlooks, and lifestyles. Apparently musical theatre, like politics, makes for strange bedfellows.

hat incomparable team of songwriters, Lorenz Hart and Richard Rodgers, author and composer of Blue Moon, began turning out their great song hits without the benefit of Necessity, the mother of so much of our musical invention, being around to spur them on.

hat incomparable team of songwriters, Lorenz Hart and Richard Rodgers, author and composer of Blue Moon, began turning out their great song hits without the benefit of Necessity, the mother of so much of our musical invention, being around to spur them on.Nor did they hear the wolf howling at the door. But they did suffer a terrible urge to express themselves in their work.

Hunger for approval, thirst for accomplishment. Haven’t you too, often experienced that feeling?

We called upon Lorenz Hart in his spacious, luxurious apartment overlooking Central Park.

He greeted us in his huge music room with Kiki, his nine-year-old dog, romping at his feet.

“She’s just home from the Doctor’s,” said Hart. “Had to take her—she was losing her hair. She’s a Chinese chow.”

I picked up my pencil.

“Don’t say anything about poor Kiki, she hates publicity,” said Hart.

Hart is hospitable and generous. “What will you have?” he said, leading the way into his ultra-modern study and offering everything from Bourbon to coffee.

“A story about you and Rodgers,” we answered.

“How did you happen to begin writing songs with ‘Dick’ Rogers?”

In his inimitable way, Hart began: “We met while Dick was attending Columbia University. I’d been out of the Columbia School of Journalism for a year or two. Of course, we decided to write the college varsity show.”

“What was the name of it?”

“Something like Fly With Me—a great success”

“What work had you done before you met Rodgers?”

“I had produced a play by Henry Myers, The First Fifty Years. There were two characters played by Clare Eames and Tom Powers. We took in so little money, we couldn’t afford to pay the players. It ran for six weeks. We’d have been worse off if it had run 12. Lost our money.

“However, after our Columbia show, Dick met Herbert Fields, a son of Lew Fields of the famous Weber and Fields Minstrels.

“Lew Fields was putting on The Poor Little Rich Girl, so Herbert asked his father to use some of our songs. By the time the show opened all of the songs were ours.

“The Poor Little Rich Girl ran 22 weeks on Broadway. Rodgers was then only 17. Of course we felt that we had arrived. We expected the managers to make us some offers. But no offers came.

“We put on amateur shows, benefits, and did anything we could to make a few dollars.

“Finally with Herbert Fields writing the book, Dick and I sat down and wrote a musical comedy. Then for months we made tours of auditions. Some managers liked the music and hated the lyrics, some loved the lyrics but couldn’t hear the melodies. Nobody took it.”

“What did you call it?”

Oh, it had some awful names. Then we all three wrote The Melody Man for Lew Fields. He took it on the road. Yes, it was a colossal—failure,” he finished.

We showed Dearest Enemy to Max Dreyfuss. He liked it, and now signed us up on his staff.

“This was in the month of March. The show could not open until Fall. We were unknown—and now very, very broke.

“We wrote Garrick Gaieties in a week. We used two or three numbers that we had been peddling around. One of them was Manhattan.

“At the opening matinee, I stood in the back of the theatre with a young writer about town, Walter Winchell. Three boys came before the curtain and recited that polysyllabic lyric! I felt like the thing was doomed.

“But that matinee, because of the long applause, lasted until seven o’clock.”