We love us some Glenn Miller, but he does seem, let’s face it, sort of buttoned up. Not exactly loosey-goosey, our Glenn. And his reputation persists as having been something of a no-nonsense guy as a bandleader, too. His music was heavily charted, with limited room for improvisation, but it obviously paid off: His orchestra was incredibly successful.

We love us some Glenn Miller, but he does seem, let’s face it, sort of buttoned up. Not exactly loosey-goosey, our Glenn. And his reputation persists as having been something of a no-nonsense guy as a bandleader, too. His music was heavily charted, with limited room for improvisation, but it obviously paid off: His orchestra was incredibly successful.

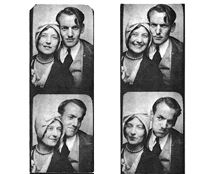

Still, we got a kick out of these 1929 photo-booth strips, taken with his (then) new bride, Helen (who, while plenty cute, doesn’t look a thing like June Allyson). Nice to see stiff ol’ Glenn mugging it up for the camera (click the image to see a larger view with more images or click here for the supersized version).