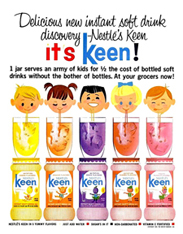

When we were kids—eight or nine years old—there was a powdered drink mix (think Tang, but in a variety of flavors) called Keen. We liked the stuff, and Mom probably figured it was no worse for us (and it was much cheaper) than soda (or pop, as we called it in Oklahoma).

When we were kids—eight or nine years old—there was a powdered drink mix (think Tang, but in a variety of flavors) called Keen. We liked the stuff, and Mom probably figured it was no worse for us (and it was much cheaper) than soda (or pop, as we called it in Oklahoma).

We can recall a conversation with our grandmother—Mom’s mom—in which she told us, as we mixed a tasty glass of Keen (which flavor? Let’s say … grape), that, when she was a youth, “keen” was a slang word, the equivalent of “groovy” (this discussion took place in the late 1960s).

Not surprisingly, considering our age at the time, we didn’t find Grandmother’s little story of much interest (though we hold out hope that we were polite enough to at least pretend we did). But now, of course, we do.

Grandmother was born in 1904, meaning she came of age smack dab in the middle of the Roaring 20s. So, of course (ain’t it always the way?), we’d give our eye teeth to speak to her now about what it was like to be a young adult during the Jazz Age, but alas, she left us some years ago, long before it occurred to us to make the connection, so we never got to have that discussion.

Grandmother was born in 1904, meaning she came of age smack dab in the middle of the Roaring 20s. So, of course (ain’t it always the way?), we’d give our eye teeth to speak to her now about what it was like to be a young adult during the Jazz Age, but alas, she left us some years ago, long before it occurred to us to make the connection, so we never got to have that discussion.

We can’t quite imagine that Grandmother was wild enough in her salad days to qualify for flapper status, but who’s to say? She and Granddad got married in 1929, so she could have spent a few years sowing some wild oats before settling down. Given that she grew up in small-town Oklahoma, though, it seems not all that likely. (That’s Grandmother standing just behind my grandfather in the photo to the left, but that shot was snapped in 1936 or ’37, which would put Grandmother in her early thirties. That’s Mom, age 3 or 4, in the lower left corner).

So, you might ask, what brought on all this spate of musing about a brief conversation regarding 1920s slang that took place more than forty years ago?

We came across the following 1928 recording by Eddie South and His Alabamians, that’s what. The song is “That’s What I Call Keen” (lyrics by Gus Kahn; music by Ted Fiorito

).

That’s What I Call Keen

Look at those eyes; look at those nose.

Look at those hats; look at those clothes.

That’s what I call keen.

Look at that style; isn’t it nice?

Look at that smile; look at it twice.

That’s what I call keen.

When I saw her first, I nearly fainted.

And I’ve been unconscious since we got acquainted.

Look at her now, looking at me.

Isn’t that love, couldn’t you see?

That’s what I call keen.