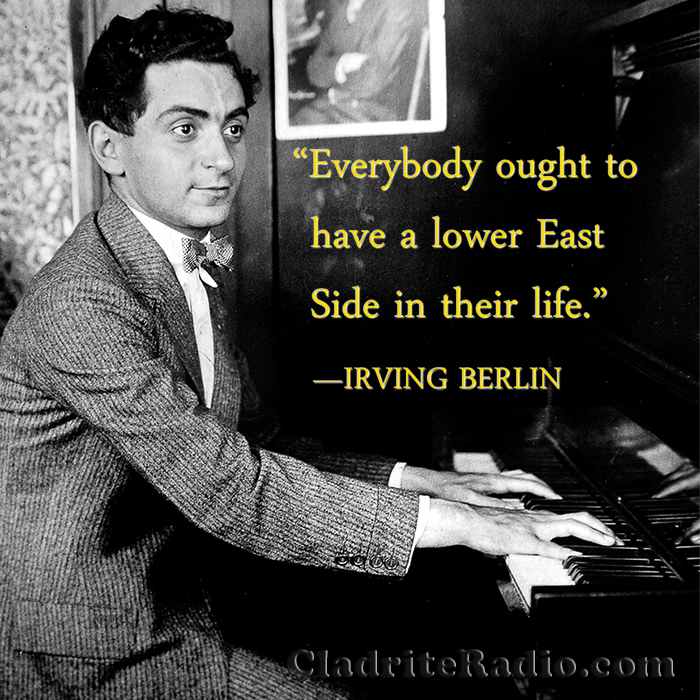

The immortal Irving Berlin was born Israel Isidor Baline in Tolochin, Russian Empire, 129 years ago today. The great Jerome Kern once said of Berlin, “Irving Berlin has no place in American music—he is American music,” and we couldn’t agree more. Perhaps no songwriter’s works are heard more often on Cladrite Radio. Here are 10 IB Did-You-Knows:

- Berlin’s father, Moses, a cantor in a synagogue, moved his family to New York City when Irving was five to escape anti-Jewish pogroms. Berlin said his only memory of Russia was lying on a blanket by the road as a young child and watching the family home burn to the ground.

- Moses, unable to find work as a cantor, worked instead in a kosher meat market near the family’s home on the Lower East Side and gave Hebrew lessons on the side. He died when Berlin was just 13. Irving began working as a newsboy at age eight, hawking The New York Evening Journal, and his mother, Lena, worked as a midwife.

- While selling papers on the Bowery, Berlin was exposed to the popular music of the day pouring out of the neighborhood’s saloons and restaurants. He began to sing some of those songs as he sold papers, and picked up some spare change from appreciative customers in return.

- At 14, feeling he wasn’t contributing enough to the family’s welfare, he moved out, spending his nights in a series of lodging houses along and near the Bowery. He at first made his living stopping in saloons and singing songs for tips, but before long, he took a job singing at Tony Pastor’s Music Hall in Union Square and at 18, he got a job as a singing waiter at the Pelham Cafe in Chinatown. All the while, he was teaching himself to play piano during his off-hours.

- Berlin’s first hit, Alexander’s Ragtime Band, created a ragtime craze that reached even his native Russia.

- It’s estimated that Berlin, one of the few songwriters of his era who composed both lyrics and melody, wrote as many as 1,500 songs, including the scores for 19 Broadway shows and 18 Hollywood films. His songs received seven “Best Original Song” Academy Award nominations, with White Christmas, written for the 1942 picture Holiday Inn, earning Berlin an Oscar.

- Berlin was not a fan of Elvis Presley‘s recording of White Christmas, going so far as to send a letter to the nation’s top radio stations, requesting that they not play it over the air.

- All Berlin’s songs were written solely on the black keys of the piano, which is the key of F Sharp. His specially constructed piano had pedals that changed the key for Berlin.

- Berlin’s hit song Easter Parade was a reworking of one of his earlier songs, Smile and Show Your Dimple.

- Despite his association with the holiday, Christmas was a bittersweet day for Berlin, whose infant son, Irving Berlin, Jr., died on Christmas 1928 of typhoid fever.

Happy birthday, Irving Berlin, wherever you may be!