In this chapter from his 1932 book, Times Square Tintypes, Broadway columnist Sidney Skolsky profiles theatrical producer A. H. Woods.

SAMUEL HOFFENSTEIN’S CREATION

A. H. WOODS. His real label is Albert Herman. Without knowing a thing about numerology, he made his name initials. Then added the tag of Woods, taking it from N. S. Woods, an actor whom he worshiped.

Was a billposter. His real entry into show business was when he took a piece of lithograph paper to Theodore Kremer. Commissioned him to write a play about it. The picture was of the Bowery. Kremer had the measles at the time. The finished product was The Bowery After Dark.

His favorite combination of colors is yellow and black.

All his business correspondence ends with: “With Love and Kisses.”

Owen Davis used to write two plays a week for him. Still considers Bertha, the Sewing Machine Girl and Nellie, the Beautiful Cloak Model, the two best plays Davis ever wrote. Davis doesn’t.

Believes any play Samuel Shipman writes in Atlantic City is worth reading.

He hired his own Boswell in the person of Samuel Hoffenstein, who now does things in praise of practically nothing. Instead of recording the actual doings Hoffenstein allowed his imagination to write the life of Woods. Thus a character was created. One which he often tries to live up to. He believes what he read.

He sits with both feet resting on the chair.

Wore a dress suit only once in his life. It was at the opening of the Guitrys. He hired it for the occasion. Is very proud of the fact that Otto Kahn said he looked good.

He believes in luck and does most everything by hunches.

William Randolph Hearst practically produced The Road to Ruin for him without knowing it. Hearst gave him $500 to move out of one of his buildings. With this he started anew.

Will get up from his desk after a day’s work and depart for Europe with all the thought and preparation that you give to going to a movie.

Has made numerous trips to Europe with only a toothbrush in his pocket. While on the ship he occasionally worries where he is going to get the toothpaste.

He reads six plays a day. Will often buy a play by merely hearing an outline of the plot.

Once walked into Hammerstein’s Victoria Theater. Saw a pretty girl on the stage. Became quite enthused. Decided that a girl so beautiful deserved to be starred in a legitimate play. The girl was Julian Eltinge. He went through with it anyway.

Has a clay statue of a negro youth in his office for luck. In the hand of this youth he always places a copy of the script of his latest production.

Walter Moore is his best friend. For this there is a penalty. He is his companion on most of the sudden trips.

He uses the most profane language without quite realizing what it means. The rougher his language the better he likes you. When he talks pleasantly keep away.

His office is decorated with artificial flavors.

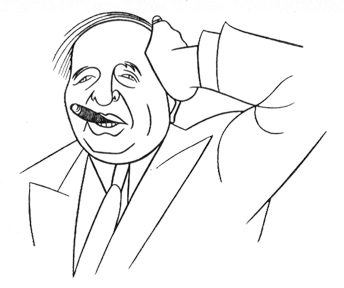

Every month he orders a thousand cigars. He chews a cigar more than he smokes it. Everybody always knows what part of the building he is in. He leaves a trail of ashes.

He knows George Bernard Shaw personally and calls him Buddy. There is no record of what Shaw calls him.

Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford and Charlie Chaplin worked for him before they entered the movies. He let them go because they wanted more money. He let them go because they wanted more money. Chaplin was getting twenty-five dollars a week and asked for thirty.

His favorite eating place is his office. Every day he has vegetable soup, apple pie and milk sent to him from the Automat. The actual time it takes him to eat this is one minute and twelve seconds.

In the summer he sits on a camp stool outside of his theater, the Eltinge, watching the audience enter.

A good script, he considers, is one that makes him forget his cigar has gone out.

During the rehearsals of The Shanghai Gesture, the cussing, hard-boiled Mr. Woods blushed and had the author tone down some of the lines.

Buttons are always missing from his overcoats.

Once considered producing Shaw’s Back to Methuselah. This play takes three days for one showing. He rejected it saying: “I’m too nervous. I’ve got to know the next day if I’ve got a hit.

At the foot of his desk there is a cuspidor. He generally misses.

He is afraid of the dark. He sleeps with the lights on.