Here are 10 things you should know about John Litel, born 131 years ago today. After a successful stage career, he became one of Hollywood’s busiest actors in both pictures and television.

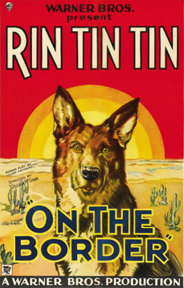

Tag: Rin-Tin-Tin

10 Things You Should Know About Jobyna Ralston

Here are 10 things you should about Jobyna Ralston, born 123 years ago today. She’s best remembered today as a leading lady in some of Harold Lloyd‘s best films, but she enjoyed a varied, if brief, career in the 1920s.

365 Nights in Hollywood: The K-9 Mystery

Jimmy Starr began his career in Hollywood in the 1920s, writing the intertitles for silent shorts for producers such as Mack Sennett, the Christie Film Company, and Educational Films Corporation, among others. He also toiled as a gossip and film columnist for the Los Angeles Record in the 1920s and from 1930-1962 for the L.A. Herald-Express.

Starr was also a published author. In the 1940s, he penned a trio of mystery novels, the best known of which, The Corpse Came C.O.D., was made into a movie.

In 1926, Starr authored 365 Nights in Hollywood, a collection of short stories about Hollywood. It was published in a limited edition of 1000, each one signed and numbered by the author, by the David Graham Fischer Corporation, which seems to have been a very small (possibly even a vanity) press.

Here’s “The K-9 Mystery” from that 1926 collection.

Fooling the public—what a great thing!

P. T. Barnum started it. Now there are over a million imitators.

Such is life!

What does it all mean?

(You probably say: “Ask Dad, He Knows,” which is a very good answer.)

You have all heard of a famous dog star?

If you have not seen him in pictures, you have at least heard of him.

Wonderful, you say.

Yes, perhaps. But listen!

The other day I visited some canine kennels and saw a number of clever dogs perform.

What I mean by perform is that they did routine work which displayed more than ordinary dog intelligence. I was amazed.

I asked the trainer about his dogs and also about the particular dog star.

He laughed.

“Why, that dog is dead,” he said calmly.

“Impossible!” I cried.

“Why”

I couldn’t say, but it did seem impossible.

“When did he die?” I asked.

“Some time ago.”

“There was no word of it in the papers.”

“There won’t be either,” he said dryly.

“I can’t see the reason why.”

“Well,—” He sat down on a box while the dogs played around him. “I’ll explain. You seem to be kinda dumb on the ways of enterprising people.”

I sat down on that.

“Well, supposin’ they went and announced that the dog had died. There would-a been a lot of silly sad remarks and millions of dollars would-a been wasted. The company back of the dog has spent heaps o’ dough puttin’ the hound over, and there was plenty of other curs which looked enough like him to take his place. Get the idea?”

At last a light dawned.

“So,” he continued, “they just kept his death a secret and got another dog to do his stuff, under the same name. The new hound is better than the first, I don’t mind tellin’ you, and they’ve got a bigger to make a pile o’ jack. You see, I know all this, because I bred the dog.”

That’s the canine mystery.

Times Square Tintypes: Dorothy Gish

In this chapter from his 1932 book, Times Square Tintypes, Broadway columnist Sidney Skolsky profiles stage and screen actress Dorothy Gish.

ISN’T SHE SWEET!

DOROTHY GISH. She is five feet four inches. Weighs a hundred five pounds. Wears a size four shoe. She has gray eyes. When she wears a blue hat, however, they appear bluish.

Is the proud possessor of six first editions and an original letter from Byron, denying that he wrote “The Vampire.”

The Gish girls, still in pigtails, began their theatrical careers touring the country in “10-20 and 30” melodramas in the days when movies were not only unheard of but also unseen.

Her first rôle was Little Willie in East Lynne. Her next appearance was with Lillian Gish in Her First False Step. Lillian played the rôle of Her First False Step. She was the Second False Step.

Doesn’t know a thing about cards. Consequently, she doesn’t play. She calls clubs, clovers.

For the last seven years she has been married to James Rennie.

Is not athletically inclined. Would much rather go shopping than play golf or tennis.

She is happiest when traveling. Will take a long trip on the slightest provocation. Many times she has left a happy home, almost on a moment’s notice, to sojourn in Italy, France, England, Cuba, and Rising Sun, Ohio.

She attended school for only two years. Reads omnivorously to make up for this. Read Schopenhauer when she was fourteen.

When she appeared in New York recently everybody asked her, “How’s Hollywood?” She hasn’t been in Hollywood since 1919. She has been working in studios in Italy, England, France and New York.

Is terribly superstitious. The first thing she does when she arrives in a town is to look up the local fortune teller.

She has never seen a prize fight, a Bernard Shaw play, Rin-Tin-Tin, a bicycle race, a Turkish bath or Van Cortlandt Park.

Every night before retiring she washes her stockings.

Very seldom attends the movies. Has seen only six pictures during the last two years.

Has had her hair treated by the same hairdresser for the last ten years. No matter where she may travel the hairdresser goes along. When playing in a picture she will not change her hair to fit the role but wears a wig.

She believes that all man should be tall, dark and handsome.

Her favorite drink is a frosted chocolate. And that tastes simply horrid to her unless she can sip it through a straw.

Made most of her big pictures abroad. Nell Gwynn and Madame Pompadour were made in England. Romola was made in Italy. The Bright Shawl in Havana.

In 1917 she was in France making Hearts of the World. She survived ten air raids.