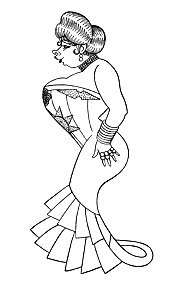

In this chapter from his 1932 book, Times Square Tintypes, Broadway columnist Sidney Skolsky profiles actress Mae West.

GO EAST, YOUNG MAN, GO EAST

MAE WEST. She was born in Brooklyn, August 17, 1900, according to her life insurance policy and the record on the police blotter at Blackwell’s Island. Several acquaintances claims to have known her before that date.

Years ago she played the Palace in “Songs, Dances and Witty Sayings.” She is the originator of the shimmy. Discarded it before Gilda Gray and Bee Palmer took up the sway.

All her leading men have been six footers. She prefers the “he-man” type.

Doesn’t smoke. The cigarettes she smokes on the stage are denicotinized.

Her conversation bubbles with slang. Will often invent certain phrases and expressions all her own. Also will render an original pronunciation of a word. When talking she covers a world of territory by continually saying: “Know what I mean.”

Her ears are really beautiful.

She has a brother and a sister. Her father was a prize fighter. Later a bouncer at Fox’s Folly Theater.

Besides English, she speaks German, French and Jewish.

Her first big rôle was with Ed Wynn in Sometime. Later she appeared in Ziegfeld and Shubert revues. In one of these she was Cleopatra and shimmied in a number called “Shakespeare’s Garden of Love.”

She always wears a pendant in the shape of a champagne bottle.

She has the same mannerisms offstage as on. When acting, however, her voice is three times lower than usual.

In writing a play she needs only an idea. After making a few rough notes she calls a rehearsal. A script is not essential. She writes the dialogue and works out the situations during rehearsals to fit the cast she has hired. Will often ask the actors if they like a certain line. If they don’t she will change it. Reading a part, she believes, makes an actor self-conscious. Before she wrote plays for herself she learned her rôles by having them read to her.

As a kid she was dressed in Little Lord Fauntleroy clothing.

Her favorite dish is kippered herring.

She likes everything massive. Her furniture, bed, even her car is larger than the average. The swan bed used in Diamond Lil was taken from her home. Formerly it belonged to Diamond Jim Brady.

She has never tried to reduce.

Seldom reads. When a public event like the Ruth Snyder case interests her she has it read to her. When she does read, it is an ancient history book.

Is of the opinion that Sex will become a classic. That in time it will be revived likes Ghosts or Hamlet.

She sleeps in a black lace nightgown. Lying flat on her back with her right arm over her eyes.

Some day she hopes to own leopard for a pet.

Her ambition is to write a Pulitzer Prize play.

She receives at least four proposals of marriage a week. And from some of the town’s best blue blood.

When dressing she first puts on her shoes and stockings. Then combs her hair and puts on her hat. Then she puts on her dress. All her dresses are made to order with special slits to enable her to do this. They are all cut very low about the neck.

In vaudeville she also worked in an acrobatic act. She can lift a 500-pound weight. She can support three men each weighing 150 pounds.

She kisses on the stage with all the fervor that she does off. During an intense love scene in the play her pulse will jump twenty-eight beats.

Her pet aversion is a man who wears white socks.

She has a colored maid who is a dead ringer for her. She will color her own photograph to show a visitor the likeness.

She believes virtue always triumphs over vice.