In this chapter from his 1932 book, Times Square Tintypes, Broadway columnist Sidney Skolsky profiles Patrick “Patsy” Cain, a man who made a living storing the scenery from closed Broadway shows.

NOT A SHOW IN A CARLOAD

An author spends months writing a play. A producer stakes everything on it. Days and nights of weary rehearsals with stars sweating. The play opens. Evening dress and silk hats. Speculators selling tickets on the sidewalk. Everybody is so happy. A few months later a truck backs up at the stage door. The path of glory leads but to Cain’s.

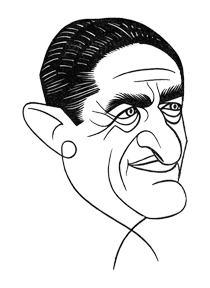

He attended P. S. 32. Bows his head shamefully when admitting that he didn’t have the honor of receiving a diploma.

His father, John J. Cain, a former policeman, started the trucking business forty-two years ago. He used to help his father just for the ride.

Seldom goes to an opening night. Producers, considering him a jinx, shoo him away. He has attended more closing nights than any other man in the world.

Has a broken nose. This he received in his youth during a block fight.

His warehouse is located at 530 West Forty-first Street. Directly opposite is an old brewery with a statue of a fallen man holding a schooner of beer. He seems to be saying to those show entering their final resting place: “Here’s to Better Days.”

Is happily married and the proud possessor of four children. Has his own home in Flushing. It was built especially for him by a stage carpenter.

He doesn’t drink, smoke or use profane language.

Rarely eat in restaurants. Has breakfast and dinner at home. Has lunch at his sister’s, who lives two blocks from his place of business.

The storehouse consists of five stories and a basement.

The fifth floor is for the shows of Aarons and Freedley, Schwab and Mandel, Gene Buck and the personal belongings of W. C. Fields and Laurette Taylor. The fourth floor holds the last remains of Florenz Ziegfeld‘s Follies and George White‘s Scandals. Their mighty efforts for supremacy rest in peace. The third floor is for Sam H. Harris, Douglas Fairbanks, A. L. Erlanger and the Paramount Theatre. The second floor is occupied by Richard Herndon and others. The basement is for the canvas “drops.” They are rolled neatly and lie row on row. Their tombstone is an identification tag on which is scrawled in pencil: “Garden Drop—Follies—1917.”

He drinks two chocolate ice cream sodas every day. On Sunday evenings he takes the entire family to the neighborhood drug store and treats them to sodas.

Employs only four men—a night watchman, a day watchman, a bookkeeper and a superintendent. He hasn’t a secretary. But the superintendent, attired in greasy overalls, takes great pride in referring to himself as “Patsy’s typewriter.”

He hires his help by the day. Employs exactly the number he needs for that day’s work. While on a job if the men eat before three o’clock they must pay for the meal. If they eat after three he must. Every day he phones his men at exactly one o’clock and says: “Boys, I think you ought to knock off now and get yourselves a bite to eat.”

He has eight gold teeth in his mouth. They make him look dignified.

Reads only two things. They are the dramatic reviews and the cartoons in the New Yorker.

Has the same amount of strength in his right hand as in his left. He can write just as unintelligibly with both.