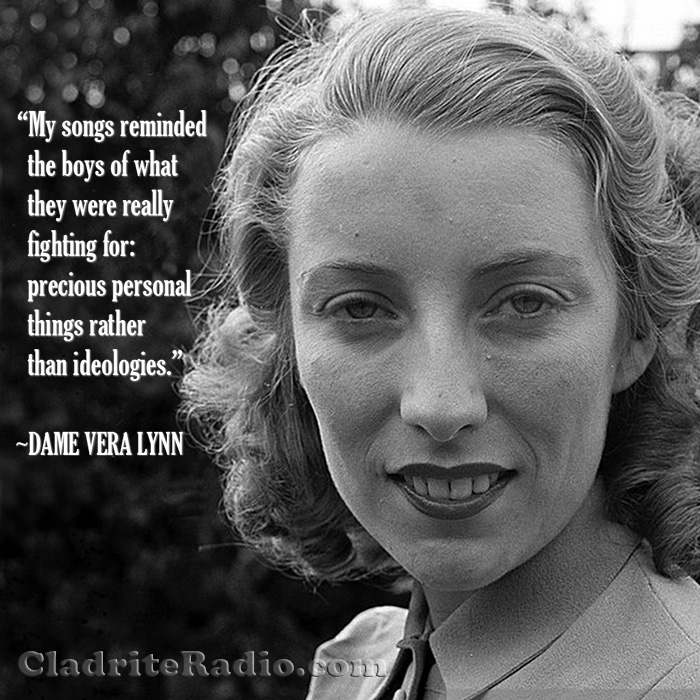

The wonderful Dame Vera Lynn was born Vera Margaret Welch in East Ham, Essex, 100 years ago today! Here are 10 VL Did-You-Knows:

- On March 17, 2017, Lynn celebrated her centenarian status by releasing a new album, Vera Lynn 100, breaking the record she set at age 97 to remain the oldest person to ever release a new album.

The album comprises some of her most beloved hits with her original vocals set to new re-orchestrations, with the addition of vocals from a number of contemporary British performers.

- On March 18, a charity concert at the London Palladium featuring some of Britain’s best contemporary talent paid tribute Dame Vera and her remarkable life and career. Queen Elizabeth was in attendance.

- Lynn was performing for audiences by the tender age of seven (which means she’s been in show business more than 90 years) and by 11 had taken a stage name, Margaret Lynn (she later returned to her given first name, Vera).

- She first performed on the radio, with the popular Joe Loss Orchestra, in 1935, and in 1936 released her first solo recording, Up the Wooden Hill to Bedfordshire.

- Lynn is best remembered today for her moving renditions of sentimental wartime favorites, such as The White Cliffs of Dover, A Nightingale Sang in Berkeley Square, There’ll Always Be an England, and her signature song, We’ll Meet Again. She further supported the war effort by hosting her own radio program, Sincerely Yours, on which she performed songs that were requested by soldiers and sailors. She also visited hospitals to meet with new mothers so that she could send their husbands who were serving overseas messages of love and support.

- Known during the war years as “the Forces’ Sweetheart,” Lynn performed for the troops in such remote and often dangerous locales as Egypt, India and Burma. For her tireless and courageous efforts, she was awarded the British War Medal and the Burma Star.

- After the war, she continued to record, topping the American charts (she was the first British performer to accomplish that feat) in 1952 with her recording of Auf Wiederseh’n Sweetheart. She was also a regular for some years on Tallulah Bankhead‘s American radio program, The Big Show.

- In the late 1960s and early ’70s, Lynn hosted her own variety television series on BBC1 and guested on a wide range of other TV programs.

- In all, Lynn placed 16 singles on the charts (UK, US or both) between 1948 and 1967. After the war, she continued to work for many worthy causes, including assisting ex-servicemen, disabled children, and breast cancer charities.

- In 1969, she was appointed Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) “for services to the Royal Air Forces Association and other charities.” In 1975, she was advanced to Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire (DBE). At age 85, Lynn founded the Dame Vera Lynn Children’s Charity, which provides support and education for families affected by cerebral palsy.

- In 2000, Lynn received the Spirit of the 20th Century Award as the Briton who best exemplified the spirit of the 20th century.

Happy birthday, Dame Vera Lynn, and many happy returns of the day!

We’re featuring the music of Dame Vera on Cladrite Radio all day long today and well into the evening, so be sure to tune in!

This story originally appeared in a slightly different form at guideposts.org.