Here are 10 things you should know about Geneva Mitchell, born 117 years ago today. A flapper if ever there was one, her life and career were eventful but all too brief.

Tag: Victor Herbert

10 Things You Should Know About Marjorie Gateson

Here are 10 things you should know about Marjorie Gateson, born 131 years ago today. She enjoyed success on stage, in films and on television.

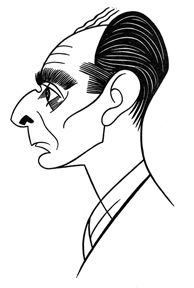

Times Square Tintypes: Ring Lardner

In this chapter from his 1932 book, Times Square Tintypes, Broadway columnist Sidney Skolsky profiles sportswriter, author, and playwright Ring Lardner.

HE’S FUNNY THAT WAY

RING LARDNER. He came to New York to do nothing and has been a failure ever since. Was born in Niles, Mich. The great event took place forty-six years ago. Always looks seven years younger than he really is.

Elmer the Great was his first play. While it was current he made his friends call him “Fanny.”

In the way of drinks his taste runs to any glass that is filled with anything but champagne. Champagne makes him nauseous.

As a newspaper man he worked in crowded offices with people talking and writing all around him. Today he can’t even begin to work if there is anybody else in the room.

He has never murdered anybody. If he does you can lay two to one that the party will be the author of a poem, story or play that is the least bit whimsical.

Occasionally he spends an entire day in a restaurant.

Was once paid five hundred dollars by a pottery concern to make a speech at their annual convention.

His first magazine story was about ball players. He sent it to the Saturday Evening Post. Not only did they buy the story but they encouraged him to write the now famous “You Know Me Al” yarns.

He’d rather be alone than with anybody excepting four or five people. He believes this is mutual.

Was among those who were the guests of Albert D. Lasker on the Leviathan‘s trial trip. While he was on the boat, he never saw the ocean.

Whenever he wants to laugh he goes to see Will Rogers, Ed Wynn, W. C. Fields, Jack Donahue, Harry Watson and Beatrice Lillie. If it is acting that he desires to see he hurries to a play with Alfred Lunt, Walter Huston, Lynn Fontanne or Helen Hayes. Otherwise he attends the opera.

He has flat feet.

Doesn’t care for parties. Unless he is giving them. Because then he can order as often as he likes.

Was fired from the Boston American in 1911. Went back to Chicago, his favorite shooting gallery, and asked the Chicago American for a job. The managing editor inquired: “What was the matter in Boston?” He replied: “Oh, nothing; except that I was fired.” The managing editor said: “That’s the best recommendation you could have. Go to work.”

Is the author of the following books: The Love Nest, What of It? How to Write Short Stories, Gullible’s Travels, The Big Town and a modest autobiography titled: The Story of a Wonder Man.

He can play the piano, the saxophone, the clarinet and the cornet. But not so good.

Has what is called “perfect pitch.” That is, he can tell which key anyone is singing or playing in without looking or asking. Once won $2 at this stunt. It really isn’t an accomplishment he can live on.

He is a passionate collector of passport pictures and license photographs of taxi drivers.

Among the things that annoy him are writing letters, answering the telephone, signing checks, attending banquets, untying the knot in h is shoelace, filling his fountain pen and trying to find handkerchiefs to match his neckwear.

Before he dies he hopes to write a successful novel. Believe he is going to live to a ripe old age.

Begins his stories with just a character in mind. Hardly ever knows what the plot is going to be until two-thirds through with the story.

He dislikes work (except the writing of lyrics), scenes like the Victor Herbert thing in the 1928 Scandals, insomnia, derby hats, beauty marks, motion pictures (excepting those Chaplin is in), dirty stories and adverse criticism—whether fair or not.

The W is for Wilmer.

He was standing at a bar in New Orleans during Mardi Gras time three years ago and a Southern gentleman tried to entertain him by telling how old and Southern and aristocratic his family was. Lardner interrupted the Southerner after twenty minutes of it with the remark that he was born in Michigan of colored parentage.

Recently he offered a cigarette concern this advertising slogan: “Not a Cigarette in a Carload.” They didn’t accept it.

He is noted for sending funny telegrams. One of the most famous is the one he sent when he was unable to attend a dinner. It read: “Sorry cannot be with you tonight, but it is the children’s night out and I must stay home with the maid.”

Times Square Tintypes: John Golden

In this chapter from his 1932 book, Times Square Tintypes, Broadway columnist Sidney Skolsky profiles theatrical producer John Golden.

“PURE AS THE DRIVEN SNOW”

JOHN GOLDEN. He’s the only man who produces clean sex plays. Yet he always manages to give the public what it wants. A shrewd showman, he realizes the value of publicity. Started the “clean” gag because of its healthy box office appeal. It has “it.”

Was once a bricklayer and the vice president of a chemical company. From the experience gained at the latter he is proficient in making gin.

Was once a bricklayer and the vice president of a chemical company. From the experience gained at the latter he is proficient in making gin.He wrote the song “Poor Butterfly,” with Raymond Hubbell and Charles B. Dillingham. In fact, his managerial career started on a song. His royalty check for “Goodbye, Girls, I’m Through,” was $40,000. Gave it to Mrs. Golden for a present. She loaned it back to him to produce Turn to the Right.

His favorite actor is Muni Weisenfrend. He never says this without adding: “And Otto Kahn agrees with me.”

Is very much interested in what makes an audience go to a play. Once distributed a circular during the run of Pigs inquiring, “What made you attend this show?” Seventy per cent of the answers were variations of “Because a friend told me about it.”

As a bricklayer he helped build the Garrick Theatre.

For the last thirty years the annual Lambs’ Washing has been held on his estate at Bayside.

He was a partner of Cohan and Harris in the production of Hawthorne of the U. S. A. His task was to pal about with Douglas Fairbanks, seeing that the young acrobat didn’t hurdle over taxicabs and climb up buildings.

He is superstitious. Likes to have a numeral in the title of his plays. Remember: The 1st Year, 2 Girls Wanted, 3 Wise Fools, 4 Walls and 7th Heaven. Considers 27 his lucky number. In roulette and other numerical games of chance he will bet huge amount on it.

He organized the Producing Managers Association. This led to the famous actors’ strike.

The man he quotes most is Ring Lardner.

Is not fussy about clothing. Never goes to a store to purchase wearing apparel. If he needs another tie, shirt or suit, he merely telephones for it.

Thinks Atlantic City and Miami are the only vacation spots worth knowing.

He is one of the few producers who treat the theater as if it were a business. Is in his office by nine every morning and leaves at five. Is in bed every night at ten. He never attends the theater in the evenings. Goes only to matinées. Misses every opening night. Even his own.

Owns the original Old Kentucky Home, having bought the Stephen Foster homestead in Federal Hill to save it from being torn down.

He realizes the value of flattery. Gets the most out of people he is associated with by using it.

His favorite tryout town is Elmira, N. Y. Believes it to be lucky and opens all his shows there.

Was the first to cover the front of a theatre with an electric sign. Did it with 3 Wise Fools at the Criterion. Then the movies took up the idea . . . And how!

He hates the word “clean.” Refrains from using it in his conversations. When it slips out accidentally, he looks embarrassed.

He has collaborated on songs with Irving Berlin, Douglas Fairbanks, Oscar Hammerstein, Victor Herbert and Woodrow Wilson.

Always puts on his glasses when he talks on the telephone.

His hobby is collecting “the key to the city.” He has framed in his office keys to twenty-seven of the most important cities in the United States.

He hates dogs and cringes when he sees one.

Has a barber shop in his office, fully equipped. Every day at twelve a barber appears and shaves him. Every other week he takes a haircut.

His home in Bayside has eight bedrooms. He sleeps in a different room each night, according to his mood.

Times Square Tintypes: George Gershwin

In this chapter from Times Square Tintypes, Broadway columnist Sidney Skolsky profiles George Gershwin, who then cast one of the longest shadows over Broadway.

By 1932, when this book was published, Gershwin had written most of the orchestral works that remain so celebrated today, including Rhapsody in Blue (1924), Piano Concerto in F (1925), An American in Paris (1928), and The Second Rhapsody (1931), and had experienced great success on Broadway with such shows as “Oh, Kay!” (1926), “Strike Up the Band” (1927), “Funny Face” (1927), “Girl Crazy” (1930), and “Of Thee I Sing” (1931).

“STRIKE UP THE BAND”

A man of note. George Gershwin.

Suffers from indigestion. Every night before retiring he takes agar-agar, a new medicine.

Was born in Brooklyn, September 16, 1898, and came to this country at the age of six weeks. Has two brothers, Ira and Arthur, and one sister, Frances. As a youngster he was the champion roller skater of his neighborhood.

Smokes a cigar out of the side of his mouth and wears a high hat gracefully. He didn’t start to smoke until he was twenty.

His father, Morris, because of his unconscious humor, is the life of his Gershwin parties. Morris has been designer of fancy uppers for women’s shoes, owned several cigar stores, owned a billiard parlor, owned a Turkish bath place and was a bookie. Morris also entertains by imitating a trumpet.

Took his first piano lesson when he was thirteen. At sixteen he was working for Remick’s. His boyhood idols were Jerome Kern and irving Berlin.

The thing he values most is an autographed photograph of King George of England. It bears this inscription: “From George to George.”

He wrote his first song when he was fourteen. It was a nameless tango. His second composition (now he had learned to title them) was “Since I Found You.” It was never published. His first published song, “When You Want Them You Can’t Get Them And When You’ve Got Them You Don’t Want Them,” he sold to Harry Von Tilzer for five dollars.

Twice a week he visits an osteopath.

Hates cards. His favorite game is backgammon. Occasionally he shoot craps.

He once worked as relief pianist at Fox’s City Theatre. Was fired because an author complained that he didn’t know how to play the piano.

An English publisher sends him copies of rare and first edition of such authors as Galsworthy, Shaw and Barrie in return for an occasional song.

His first piano teacher, whose memory he cherished, was Charles Hambitzer. His present teacher is Mme. Boulanger in Paris. The first time he went to Paris to study he came back with a trunkful of shirts and ties. On his last trip he returned with a $10,000 organ which he has yet to unpack.

Hard liquor doesn’t appeal to him. He likes a glass of real beer. After more than one cocktail his eyes begin to shine.

The first long piece he ever wrote was not “The Rhapsody in Blue.” But one called “135th Street.” It was performed by Paul Whiteman in the Scandals of 1921 for one performance only. It was taken out because it was too sad.

He is very particular about his clothes which are made to order. Even when he made only $25 a week he spent $22 for a pair of shoes.

Writes whenever the mood seizes him. He may have just returned home after a party and still attired in his evening clothes he will sit down at the piano. Or he may compose wearing pajamas, or a bathrobe—or even nude.

He is physically very strong. Especially his arms which are powerful. He is a swell wrestler.

His brother Ira writes the lyrics for his songs. Before, Irving Caesar and Buddy De Sylva had the honor.

“The Rhapsody in Blue” was played for the first time, February 12, 1924, at Aeolian Hall. It took him three months to write it. It took him eight months to write “An American in Paris.” His first real popular hit was “Swanee.” This was written for the revue that opened the Capitol Theatre.

Is bashful about playing the piano at parties. He has to be coaxed. Once he starts, however, you can stop him. He says, “You see the trouble is, when I don’t play I don’t have a good time.”

In the volume called Great Composers As Children he is the only living composer listed.

One evening the family discussing the new Einstein paper. George expressed his surprise at the compactness of the scientific vocabulary. He said: “Imagine working for twenty years and putting your results into three pages?” “Well,” said Papa Gershwin, “It was probably very small print.”